We are losing a soccer field of seagrass every 30 minutes

Declining Posidonia meadows

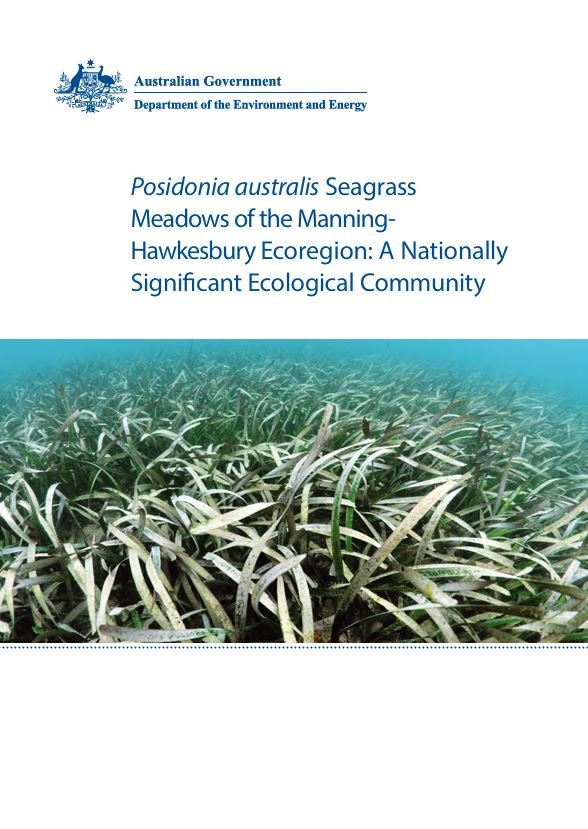

Posidonia australis is a beautiful and slow-growing plant that forms extensive underwater meadows all over southern Australia, from Wallis Lake in New South Wales to Shark Bay in Western Australia.

Like us, there is a range of conditions that seagrasses do best in – generally, this is in clear water where they can access lots of sunlight to photosynthesise and grow, but also specific water temperatures. These requirements make seagrasses sensitive to changes in the environment. Humans change the environment a lot, and this can have negative effects on seagrass, such as through excess nutrients, climate change, boating and coastal development. For instance, dredging can rip seagrasses out, reduce the amount of light available, or bury them, making it difficult for them to grow and survive. The status of seagrasses around the world, like most things, is complicated - there are lots of places where it has declined, in some places it is stable, and in others, meadows are increasing.

In eastern Australia, Posidonia australis meadows are found in sheltered bays, which are also preferred sites for us humans: this is where we often choose to live, work and play. Increased coastal development and pollution in these sheltered estuaries have led to major Posidonia declines over the last few decades. These aerial shots over Manly, in Sydney, show the presence of just a few boat mooring scars in 1942.

By 2009, the remaining seagrass was visible as dark patches surrounded by some bare light-coloured sand where moorings scour the seafloor. Seagrass has continued to decline at an alarming rate in the last ten years. Additionally, many people are still not aware of where Posidonia australis lives, and anchor scars and damage by propellers are often visible in many meadows.

The declines of Posidonia meadows in the central parts of NSW (where most people live) have been so severe that six meadows, from Port Hacking to Lake Macquarie, shown in the map below, have been formally listed as endangered by the NSW Government (Fisheries Management Act). This means that it is illegal to harm, collect, buy, sell, or possess Posidonia australis from these areas without the proper permit, licence, or approval. Additionally, significant penalties can also be imposed for damaging their habitat through activities like dredging, land reclamation, or construction, if done without the necessary approvals.

The Posidonia australis meadows found from Wallis Lake to Port Hacking (NSW) have also been listed as an endangered ecological community by the Australian Commonwealth Government (if they meet certain criteria - see EPBC Act), which makes it illegal to take actions that significantly impact these meadows without federal approval.

There is a real risk that Posidonia may become extinct in some of the areas it is currently found within the next 15 years, unless conservation and restoration actions reverse current trends. Thankfully, coastal development near seagrass meadows is limited by these State and Federal regulations, and water quality has greatly improved in the last few decades, as we have become better at managing waste and reducing pollution.

However, many traditional block-and-chain moorings are still being installed and maintained in many bays where Posidonia meadows live. Mapping has shown that mooring scars can be very large, form quickly, and can take decades to recover once a mooring is removed. Traditional swing moorings disturb not only seagrasses but also other organisms living in the seafloor, leading to bare patches. Below photos credit: Kingsley Griffin.

Mooring scars are visible from the water’s surface. Across all of NSW, currently leased moorings are causing losses of around 130,000 meters squared (that is more than 26 soccer fields!), but the real loss is even greater, as many estuaries contain old scars that remain after the relocation of moorings.